|

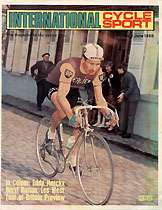

International Cycle Sport | June 1968 | Issue No 2 | Page 4 International Cycle Sport | June 1968 | Issue No 2 | Page 4

Although Bordeaux-Paris is known as the "Derby of the Road," it is Paris-Roubaix which annually provides the great Derby between French and Belgian riders, the manufacturing town of Roubaix being only a few miles from the frontier. This year the "visitors" were completely in command Belgians filling the first five places of a testing race over atrocious roads, with world champion Merckx first over the line.

JEAN STABLINSKI SHOWS THE WAY FROM PARIS TO ROUBAIX

by J. B. Wadley

Just before ten o'clock on the morning of Sunday 7th April, 1968, I was a passenger in one of the long line of Press cars cruising slowly in front of a field of 135 riders making their way from the assembly area to the official start of a road race. On looking back at the brightly coloured pack I noticed the sign welcoming travellers to the pleasant town we were now leaving: "Chantilly, City of the Horse" it said. Race horses, of course. Chantilly might be called the Epsom of Paris. But the entries about to come under the starter's orders were today engaged in the greatest of all single-day cycling classics, Paris-Roubaix, the race which starts like a Derby on the fine flats roads of the Oise and the Aisne and ends with a Grand National slam over the vilest roads that can be found in French Flanders.

In the old days Paris-Roubaix, logically enough, used to start in or very near Paris, the route making for the Franco-Belgian border by the shortest possible route. If any diversion was made it was to take in stretches of good road to avoid the dreadful cobblestones. Since the war this pave has gradually disappeared and in recent years the organisers have literally been taking for trouble to give Paris-Roubaix its traditional character. If they did not do so, they said, the race would became the easiest in the world instead of the toughest. But as new stretches of cobbled roads were discovered and included in the ever-changing route of Paris-Roubaix, so did the local highways departments take umbrage at the resulting publicity and quickly transform the corrugated purgatory into smooth bands of concrete, and therefore useless for the following year's race.

"Within two years there will be no more pave in northern France, and Paris-Roubaix will not be worth running" So said the pessimists. Others had different ideas. "Don't you believe it. If you want to see real old-fashioned pave, just follow me." The speaker was Jean Stablinski, the ex-world road champion who lives at Valenciennes. In the winter Jean is a great man for shooting, and he said he knew dozens of roads through the woods as bad as any that had been used since the first Paris-Roubaix was held in 1896.

'And so Stablinski was invited to join the organising committee of the 1968 race, and from what we had heard and read in the newspapers, he had not been kidding. "Only 30 at the most will finish this race" said one newspaper. "Even less if it rains." Another quite seriously said that a rider changing on to a bike with a sprung saddle, well padded handlebars and fat wired-on tyres, at the start of the "northern hell" would stand a good chance of finishing in the first ten, One official even thought that if the weather was really bad, no rider would finish at all . . .

None of these forebodings had any effect. All the stars were there just behind us, riding slowly in a pack, waiting for M. Jacques Goddet to set them on their way. And one of the 135 was the villain himself, Jean Stablinski, the man whose research would be bringing so much pain and suffering to his companions on the road - and joy to the man who was destined to win the most coveted of all classics. M. Goddet drops the flag, and they are off . . .

When I report Paris-Roubaix I like to be on the job the day before the race itself picking up all the gossip and generally soaking in the atmosphere. This year, however, it was not possible. I did not arrive in Paris until midnight Saturday, and only got to Chantilly half an hour or so before the start. But my colleague Jean Payen of Lille, whose guest I was in the Nord Eclair car, put me in the picture.

"Most interesting point was yesterday's draw by the Directeurs Sportifs. Antonin Magne, the Mercier boss drew No 1. That means he will be first in the line of team cars. On these wide roads we are now on, of course, that doesn't mean a thing. But in the "northern hell" it will be a priceless advantage. I have been over the roads and some of them are just beyond words and wide enough for only one car. So if Poulidor punctures in the leading group Magne will be right behind to change his wheel. Hard luck on the fellow puncturing whose car is in 12th position!" "Good for Poulidor" I said "But what about Barry Hoban? He's a Mercier man, too, you know!" "Yes, of course." my friend apologised "I admire Hoban very much. He was 12th in last week's Tour of Flanders and any rider who can finish in the same time as Merckx, Janssen, Altig, Poulidor, etc. in such a tough race is quite capable of winning Paris-Roubaix where chance plays such an important part." "So Poulidor is in luck before the race starts" put in our driver "But Anquetil can't be so happy. His race number is 13!"

We were now on wide open roads, dipping and climbing gently so that at the crest of one little rise we could see the field spread out for our inspection two to three hundred yards behind. Just before Senlis, five miles from the start, we saw a lone rider sprinting out in front. A condition of following Paris-Roubaix is that every Press car must be fitted with a short-wave radio capable of picking up the 51 metre transmissions from the same technical organisation that is used in the Tour de France. Into our note books went the first "break" of the day: "Rider No 103, De Pra, Italy, has a lead of 100 metres," The Radio announced. Within two minutes, as we sped through Senlis itself, came the curt announcement Echappee terminee (break over). The little incident was not without significance, though, for De Pra is a team-mate of Gimondi, Paris-Roubaix winner in 1966, and this might have been part of some ambitious plan for another victory.

One advantage of "following the race from the front" and. joining the procession of cars ahead of the field, is that it is possible to slip handily behind any real break that forms. A disadvantage is that you can't see what is going on behind the main groups, although thanks to Radio-Tour you soon know about it. The next announcement was: "Puncture to Claude Guyot. He is waited for by three of his Pelforth team-mates, including Bernard Guyot." I remarked that it was a nice brotherly act, but M. Payen did not agree. "A stupid thing to do," he exclaimed. "Bernard Guyot has a tiny chance of winning Paris-Roubaix. His place is at the front, not to stooge around acting the domestique to his brother who hasn't much chance of finishing."

I argued with friend Jean that today was different, on account of the head wind. Those who have travelled the roads of Europe with me over the last 30 years will have noticed that I have a "thing" about wind and its influence on road racing. On this occasion, when I first saw the flags and smoke blowing from the north, I sensed that the average speed would not be high, not just because of the physical influence of that wind, but because of its effect on the minds of the riders.

Had there been a back wind blowing - as in 1964 Peter Post won at the record average speed of 28.25 mph - then Bernard Guyot would have been plain crazy to have stayed behind for Claude. They would have got back on, all right, to the back of the bunch that is, but during their chase a break would certainly have formed in the front. With a head wind there was little risk in the Guyot exercise. The wheel was changed slickly, and the Pelforth quartet cunningly but quite legitimately used the shelter of the following press cars (on the left of the road) and the team cars (on the right) to ride comfortably back to the still compact bunch.

|

Jean Stablinski Jean Stablinski

21-May-1932 - 22-Jul-2007

|

|

Major Victories -

1954 Paris-Bourges

1955 Paris-Valenciennes

1956 Tour of the South East

1957 Tour de l'Oise, Grand Prix Fourmies

1958 Vuelta a Espana

1960 French Road Championship, Nice-Genoa, Grand Prix of Orchies

1961 Boucles Roquevaroises

1962 French Road Championship, World Road Championship

1963 Paris-Brussells, French Road Championship, Tour de Haute Loire

1964 French Road Championship, Circuit des Frontieres

1965 Frankfurt Grand Prix, Tour of Belgium, Tour de Picardie, Paris-Luxembourg, Grand Prix Gippengen, Baracchi Trophy (with Jacques Anquetil)

1966 Amstel Gold Race, Grand Prix Isbergues

1967 Grand Prix Denain

|

|

This incident began at the hamlet of La Roue Qui Tourne (The Turning Wheel) soon after which we passed through the town of Compiegne where the 1918 Armistice was signed. Here in Paris-Roubaix the battle had not even begun, and in the first hour only 23.5 miles were covered. There was protection enough from the forests on the right side of the road, but the wind was blowing hard over the open wheat fields to the left. Just the weather for Dutchmen! One, Harings, indeed was out for a minute or so with a 200 yards lead perhaps in the hope that reinforcements would come up to form one of the "Bordures" at which the Lowlanders excel (A Bordure is what we in Britain call an Echelon). The fact that no reinforcements came did not mean that the peloton was lethargic. The opposite, indeed was the case. Stars and team men alike were very much on the alert for any such surprise build-up.

Another announcement over Radio Tour: 'The commissaires have decided that the following must submit to an anti-doping control after the race at Roubaix: The first, second and third finishers, the 13th and the 17th. It is the responsibility of the Directeurs Sportifs of the riders concerned to see that this is carried out."

And so the second hour went by, slower even than the first. There had been skirmishes, but without any real result. One little group of eight or so managed to get a 30 seconds lead, the instigator being Jose Samyn, a North of France boy who obviously meant to be in evidence on his home ground. De Pra there again, too, with another Salvarani team-mate. But behind all eyes were on Gimondi lest he should attempt to get up with his two hard working slaves.

Then at Mericourt (75 miles) the first real build-up of the race began when the Dutch born Frenchman in the Peugeot colours Van Der Linde was away pursued by Haeseldonckx (Mann-Grundig), Neri (Max-Meyer, an Italian team managed by 1960 Tour de France winner Nencini), Leblanc (Pelforth) and Casalini (Faema). These five rapidly gained on the main group, partly because none of them was all that dangerous, and partly because their team-mates were giving them some measure of protection. Then when the quintet had a 30 seconds lead out shot the familiar figure of Roger Pingeon, a crash hat over his racing cap, pedalling powerfully after them. Van Der Linde glanced back, saw his team captain coming up, dropped back a few yards, and in no time the junction was made. Six men in the lead, including two of the Peugeot team who proceeded to the front to force the pace and take the break further and further from the field.

When the lead was 1.5 minutes we stopped by the roadside, let the breakaways pass, just at the moment when an incident was taking place. Two riders were slightly off the back, Haseseldonckx blocking and chopping and generally trying to get rid of Casalini who was obviously not a working member of the party, but simply there to make a nuisance of himself on behalf of his own leader Eddy Merckx.

The presence of Pingeon at the front turned the break from being just an interesting passage of arms, to something more serious. Of all those who had been training on the course during the past few days, Pingeon was the one who had created the biggest impression. His intentions were now obvious. He meant to be well clear of the main group at the "gates of hell" at Solesmes where the real rough-stuff started. Pingeon had said in interviews that he believed that if it rained, the 70 miles from Solesmes to Roubaix would be an individual time trial, with the advantage to the man in the lead.

At Solemes the Pingeon group had a lead of 4.25 minutes and with a big black menacing cloud looming up ahead!

You will see from the sketch accompanying this article that the pave comes in sections, big black hunks of cobbles sandwiched between slices of white concrete. In some ways this is worse than having the stuff a 1.1 the way, so far as comfort is concerned. But from the point of view of progress the concrete provides an opportunity to ride fast. The "white portions" certainly contributed to the eventual downfall of Pigeon, for while on these stretches he at the front was doing practically all the work, the main bunch behind were gradually reducing his lead. I wonder if Pingeon appreciated the irony of the road sign just outside Solesmes, which said "Solesmes thanks you for slowing down. Good luck!" . . .

But still Pingeon battled on. The roads were narrow, without shelter, a rough dirt path besides the cobbled stretches. It was a do-or-die effort by the 1967 Tour de France winner. Off the back of his leading group went first Haeseldonckx, then Le Blanc, then the Faema man who lately had at least been going through when his turn came. The three of the dropped men teamed up together, and when they were 30 seconds behind Pingeon and the other two we went by them in our car, the chosen moment being on a nasty downhill stretch of cobblestones strewn with gravel chippings. In the space of 50 yards all three were off their bikes with punctures . . . "Behind in the main group, now at 2.5 minutes from Pingeon, Bracke has fallen but is not seriously hurt. Gimondi has punctured and fiVe of his team-mates wait behind for him" came news from Radio Tour. Then almost immediately "Punctures sustained by De Boever, Post, Delberghe, Gustave, Dllsmet, Hoban. Bodard and Bouqullt crash. ."

On hearing of the approach of the peloton, Ringeon decided to go it alone. His young team-mate Van Der Linde - a first year pro, - had ridden his heart out on his behalf and now had nothing left. Rattling over the pave, slithering along the dirt tracks, pedalling powerfully on the concrete, the Peugeot man pressed on and must have taken heart ten minutes later when he learnt that he was now 3.5 minutes up on the field. But over Radio Tour we had heard the reason why: a level crossing delay had held up the field for nearly two minutes. At Valenciennes, where Pingeon grabbed his musette from Gaston Plaud, he heard that his lead was down to 2.5 minutes again.

As well as giving the Press information about the race, Radio-Tour also gives us instructions: "Press cars which are now behind Pingeon should pass him in the next six kilometres. After that the road is very narrow. This is essential because the peloton is coming up fast and the road between it and Pingeon must be kept clear of cars."

We obeyed instructions. Buffetted by the wind, red in the face, Pingeon looked beaten, but defiant. He brought off the ride of his life last year in the Tour de France on a stage which started at Roubaix. Today for a time it seemed that he was going to end an equally notable ride in the same city, "Two minutes difference between the peloton and Pingeon , , .one minute, . .thirty seconds, . ," the Radio tells us "Now Pingeon punctures, changes wheels quickly, is away, but the peloton are on his heels, Pingeon is caught. Pingeon now actually leads the peloton . . ," And so the first phase of the 66th Paris-Roubaix was over. Forty-five miles still to go, of which 35 at least were cobbled.

During the last half-hour of Pingeon's courageous effort, that big black cloud has come and gone with no more bother than a few big drops to lay the dust. And dust there is in plenty. It is blown there from the hedge less fields through which the Stablinski route is winding. Most of the "white" stretches on the plan of the course are brief bits of main road off which we turned by sharp corners on to fresh examples of the kind of "road" that has not changed for 50 years, In the distance are black pyramids of coal slack; on either side of the road heaps of good old fashioned manure. Both these commodities have played a part in the construction of this unique cycle racing route: the so-called cycle paths are largely composed of coal dust; manure straw has been blown from the fields and then trapped in the considerable gaps between the granite stones.

And look at those "paths"! Once upon a time they were doubtless on the same level as the pave, and it would be possible to switch from one to the other without much trouble, But nowadays the rain drains off the pave on to the coal-dust track Which becomes a gutter, and so the "path" is on an average six inches below the granite and sometimes as much as a foot! Hard luck on the chap who decides to keep down below for suddenly he will find a recently-dug drainage channel across his path. In most races through cobbled country, the cycle paths are kept clear by the police, but here the crowds are sometimes massed along them as if to warn the riders to keep to the comparative security of the granite blocks.

Such is the setting of the final stage of the 66th Paris-Roubaix, the Flanders plain that saw less sporting battles fifty years ago.

Yet being in front on those flat roads is, from the reporting angle, rather like being on the Galibier or the Tourmalet I The road twists and often doubles back on itself so much that it is possible to stop every now and then to look across the fields and clearly see what is going on.

On one such stop we see a rider speeding away from the peloton, which is now no more than 30 strong. "Gimondi attacks" comes the message. Exciting news followed by a sad but inevitable piece of additional information: Pingeon has been dropped as the pace increases to bring back the dangerous Italian. Immediately Gimondi is caught we can see another attack developing, and this time we learn that the runaway is Cooreman, a Belgian of the Mann-Grundig team. Twenty seconds lead. . .a useful springboard. Across the fields we see a dozen riders sprinting after him in ones and twos and soon in our notebooks we have their names: Janssens, Merckx, Bocklandt, Brands, Zooltjels, Van Springel, Godefroot, Duydam, Van Schil, Gimondi, Poulidor. They are soon 40 seconds up with 35 miles to go. This could be it! But the bunch is not beaten yet. We do not know until afterwards that it is largely due to Rudi Atig that the runaways are brought back. Thirty men together again just over 30 miles from the finish. Will they arrive together at Roubaix and confound all predictions of a merciless time trial through the closing miles of hell? , Now turn, please, to the "plan of the pave and and note particularly the little portion that finishes at 211.8 kms. It is here, on a narrow and very bumpy stretch, flanked with high grass banks, that Eddy Merckx attacks, and it is not by chance that he does so. He knows the, stretch is short, and by the time his rivals realise what is happening the world champion is on the concrete and they still struggling on the granite.

Although Merckx has succeeded in getting rid of most of his rivals he is not yet ready to part company with all of them and is glad when he looks round to find three on their way to join him. First comes Edouard Sels. Not so good! Sels is one of the best sprinters in the business and quite capable of beating him on the track at Roubaix. Next is Bocklandt. No real worry here. Willy has for years always been "there" at the end of a tough road race; he'll work like a hprse over this pave and be a useful ally. Lastly there is Van Springel. A dangerous enough man-but it could be worse. Altig for instance.

But unknown to Eddy, Altig is at that moment taking an awful hiding and will soon be dropped by the chasers of whom Barry Hoban is among the most active.

So four Belgians are in the lead and are in their element, for if the organisers have to call in experts to find this sort of road in France, they themselves have been brought up on this kind of thing. On the smooth patches they relay each other powerfully like a pursuit team; on the "other" they pick their way expertly over the granite paving blocks, switching on and off the dirt paths now and then when things promise smoother that way.

Four such men - who must be among the strongest to be there at all-with the "road" to themselves have a great advantage over the two dozen group behind which includes many men who either can only just hang on, or are team-mates of the breakaway group and therefore causing general obstruction to desparate chasers like Poulidor, Janssen and Gimondi, the latter of whom punctures with the battle at its height.

By now our leading four are on the blackest of all stretches, between the 227.6 and 242 kms points, which in parts is nothing more than a farm track with gaping holes where blocks of pave used to be, strewn with mud dropped from tractor and wagon wheel, or occassionally covered with sand and gravel. On this cyclo-cross country track the four gain steadily and have now nearly a two minutes lead over the main group from which Godefroot has parted in a powerful counter-attack with one man on his wheel: Van Schil, team-mate of Eddy Merckx.

In front Bocklandt is in trouble, and no surprise at that, for last year the Belgian had a bad accident and is only just getting back to form. Soon he sits up, beaten. Now there are three. And alas, only too soon, only two for Sels punctures, changes wheels, and then punctures again almost immediately. Two riders pedalling all out for Roubaix. Merckx in the world championship jersey pushing a gear some five inches higher than the more supple Van Springel who is riding a bicycle with wooden rims which are said to be faster and more comfortable over cobbled roads. All journalists are scribbling furiously in notebooks, radio reporters jabbering into their mikes, and so is Robert Chapatte the TV man who, for the first time, is giving a direct commentary from the back of a motor-bike. There is but one theme: the "come-back" of Merckx. This seems a bit odd. For how long has Merckx been "absent"? The answer is for about a month, and that is an awful long time for a rider of his talent to be out of the picture. The facts are that Merckx took the first stage of the Tour of Sardinia in February by six minutes and easily won overall. Many of his rivals were upset at the way he emphasized his superiority and vowed to make life difficult for him by pittiless marking-Van Looy in particular. The knee, injured in Paris-Nice has been giving him trouble, too.

The Merckx-Van Springel tandem forges on, a dense crowd of spectators on either side of them, the TV helicopter zooming overhead. They are the only two in it, and know they have the race in hand. Behind Godefroot is chasing furiously; with Van Schil still on his wheel he has gone right by the distressed Bocklandt and the unlucky Sels and is gaining on the runaways. He is tremendous, this Godefroot who a week earlier won the Tour of Flanders, and not just a sprinter. He is riding so strongly that even the non-working Van Schil is eventually dropped.

Now it is time for us to leave the battle area and move quickly to the Roubaix track where we follow the last five miles of the race on the TV screen. The position is clear as we see first the Merckx-Van Springel tandem, then the energetic Godefroot, finally the beaten main group. We watch the leading pair, noting that of the two Merckx looks the more anxious, turning round every now and then to check that Goodfroot is out of harm's way. His anxiety is understandable. Everybody expects him to win.

|

Results Paris - Roubaix 1968

164 miles

|

|

1 EDDY MERCKX (Belgium) 7h 9m 26s

2 Herman Van Springel (Belgium) at one length

3 Walter Godefroot (Belgium) at 1m 37s

4 Ward Sels (Belgium) at 3m 11s

5 Van Schil (Belgium)

6 Poulidor (France) at 5m 59s

7 Nijdam (Holland) at 7m 29s

8 Janssen (Holland) at 7m 46s

9 Reybroeck (Belgium) at 8m 3s

10 Melckenbeck (Belgium)

11 Brands (Belgium)

12 Zoont (Holland)

13 Peffgen (Germany)

14 Huyssmans (Belgium)

15 Grain (France)

16 Hoban (Great Britain)

17 Correman (Belgium)

18 Genet (France)

19 Jourden (France)

20 Gimondi (Italy)

21 Hellemans (Belgium)

22 Bouquet (Belgium)

23 Riotte (France)

24 Stablinski (France)

25 Bocklandt (Belgium) at 8m 59s

26 Deloof (Belgium) at 10m 47s

27 Durante (Italy) at 16m 54s

28 Lemeteyer (France) at 18m 58s

29 Spruyt (Belgium)

30 Pietens (Belgium)

31 Stevens (Belgium) at 21m 15s

32 Planckaert (Belgium)

33 Hernie (Belgium) at 21m 33s

34 Poggiali (Italy)

35 De Pre (Italy)

36 Leman (Belgium) at 25m 15s

37 Courthoux (Belgium)

38 Steegmans (Holland) at 30m 12s

39 B. Guyot (France)

40 Samyn (France)

41 Decan (Belgium)

42 Guerra (Italy) at 40m 57s

43 Van der Linde (France)

44 Crepel (France)

All other riders retired

|

|

It will be an awful let down if he doesn't.

Now there are roars from the far side of the track. The spectators on the top terraces can see the pair a few hundred yards from the track, and within a few seconds shrill blasts of a whistle herald their entry on to the scene for the lap and a half that finishes every modern Paris- Roubaix.

It is a two-up sprint in every sense of the word, almost like Reg Harris v Arie Van Vliet. The pair are three minutes up on the pursuing Godefroot and take their time, Van Springel slowly leading the watchful Merckx. But on the last banking the world champion is in the lead, swoops down with his biggest gear and has a clear length lead over the line. As he throws his arm up in triumph I hear a Belgian radio commentator telling his listeners: "Eddy Merckx, our young cycling god, has ridden through hell to the paradise of victory in the greatest of all cycling classics."

And so, true to tradition, despite the terrors which the organisers scheme out each succeeding year, Paris-Roubaix remains the cycling steeplechase which an outsider never wins. Nor can it be said that the world champion was lucky to get through without trouble - he punctured twice. Curiously enough, despite the severity of the course, there were no serious crashes. I believe the reason for this is because of the thorough way in which the organisers kept the "battle area" clear of press cars which, I must confess, have often been responsible for causing accidents.

Victim of a minor fall was Michael Wright who thought he would have finished in the peloton without his trouble. Derek Harrison, suffering from a bad cold, was in the sag-wagon before the really bad pave started.

Barry Hoban gave me a lift into Roubaix town before he turned East for Ghent. His 16th place after two punctures was a very fine ride in such an exacting race. I asked him if he had used any special equipment for the extra bad roads. "No" he replied "All that stuff about using wired on tyres, sprung saddles and thick rubber grips on the bars was a lot of newspaper talk. But I did make one mistake by keeping on my usual 53 x 42 chainset, with the 13-17 rear block. The ideal gear for the bad pave was what we call 84 at home. To get that I had to use 53 x 17, and of course the constant bumping made the chain jump on to the 16 and 15. I noticed that Janssen had the right idea. He had 53 x 50, and he was all right with the 50 x 16 with the chain in a nice straight line. You live and learn. I ought to have known that, living in Belgium"

Next day I had lunch with Louis Debruycker and his family at their home near Lille. I expected the Bic No 1 mechanic to be up to his eyes sorting out wrecked material and to get an expert account of the special technical preparations that had been made for this exceptional Paris-Roubaix. Not a bit of it. Louis was having a day off, all the equipment had gone back to Paris, and he confirmed what Barry had said.

"The only thing M. Louviot, our Directeur Sportif, insisted on was that his riders should use 10 ounce tyres instead of 8.5. On Saturday night Sels asked me to change his back to 8.5 - M. Louviot said he could "at his own risk" - in case he was there with a chance in the final sprint. You know what happened. Perhaps Sels lost Paris-Roubaix through not taking advice," Paris-Roubaix is always an Ifs and Buts race.

But if a world champion wins there can't be much wrong with it. . . . . |