|

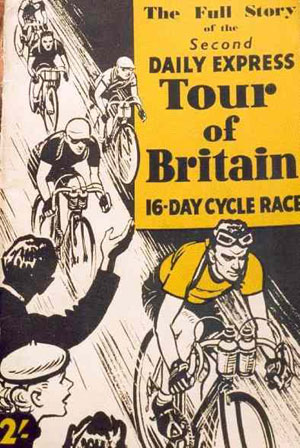

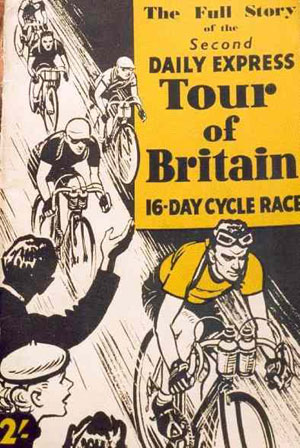

THE Second Daily Express Tour of Britain, the greatest cycle race Britain had ever seen, ended in Alexandra Palace, London, on September 6th. It was won by the man the experts said 'could not possibly win', Ken Russell, romping home on a borrowed machine for the final 30 miles, swung into the Palace grounds to the deafening roars of thousands of spectators, and finished in second place on the last stage and first place on overall general classification. THE Second Daily Express Tour of Britain, the greatest cycle race Britain had ever seen, ended in Alexandra Palace, London, on September 6th. It was won by the man the experts said 'could not possibly win', Ken Russell, romping home on a borrowed machine for the final 30 miles, swung into the Palace grounds to the deafening roars of thousands of spectators, and finished in second place on the last stage and first place on overall general classification.

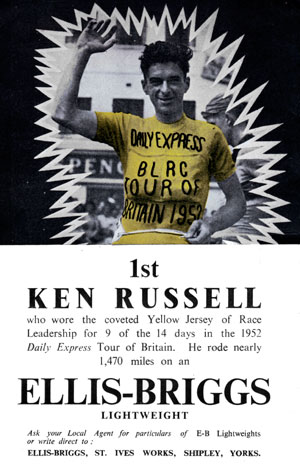

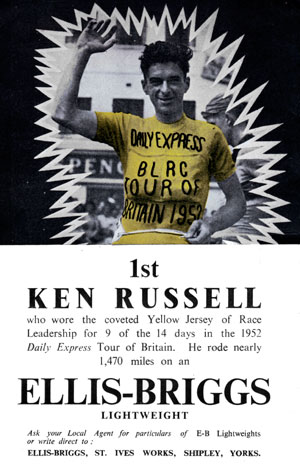

Ken, a 22-years-old salesman of the cycles he rides, had been race leader, wearer of the Yellow Jersey, for nine of the 14 racing days. Without team support, up against the combined might of the country's strongest and most highly organised teams, he held grimly to his lead over the final stages. No amount of attacking, no team tactics by others could unsettle him. Alone he met every challenge - and attacked in return.

Not only had he to ride against 'independent' (semi-professional) and amateur teams from this country, but national teams from Scotland, Ireland, France, Italy, Belgium and Germany. In addition to these six national teams, there were five ' independent ' British teams and five top-class amateur teams.

Of the Continental teams, the Belgian riders did the best. They finished in fourth place in the team race, and their best man, Marcel Michaux, filled eighth position in the race as a whole. Indeed it was Michaux who provided the most sporting gesture of the whole race. For Michaux it was who, when only 30 of the 1,470 miles remained, loaned his machine to Russell. Russell's cranks were working lose and a tyre was softening. Michaux, casting aside all chances of a personal win on the last stage (and he had set his heart on that one victory), unhesitatingly switched machines with Russell, dropping back himself to effect repairs. Among the nine teams to finish, the Scottish national team filled eighth place, and the Irish team ninth. The French and Italian teams lasted only four days, giving as their excuse 'lack of beefsteaks'.

The German team fared better, but were dogged by bad luck right from the start. Last German, Peppi Schwaiger, kept in the race until Edinburgh. The tough climb over Carter Bar on the Edinburgh to Newcastle stage proved too much for him, and he too retired.

Worst hit by bad luck were the Irish and R.A.F. teams. Day after day some misfortune would befall the Irishmen ; accidents, mechanical trouble and every adversity seemed to come their way.

The R.A.F. team could only finish two riders- a minimum of three is required to gain a team placing. Their captain, Ken Jowett, retired after crashing at Weston-super-Mare. Ron Thomson crashed later and retired, and John Fraser pulled a muscle between Nottingham and Norwich which forced him to come out of the race.

Altogether, 35 of the 78 men who started out from Hastings failed to reach the finish. This gives some idea of the toughness of the course, the fierceness of the struggle.

At such a pace, team work becomes important. It was here that the B.S.A. riders scored so brilliantly. Led by Bob Maitland, they were continually at the head of affairs. There was hardly ever a serious breakaway without at least one of their number being part of it. From the time they took over the lead in the team-race section of the event, after the fourth day, they were not once seriously challenged.

|

|

Marcel Michaux presents the trophy to Ken Russell

|

|

Opposite tactics were employed by the Sun Cycles team. After losing one of their best men in Len Wightman, who was forced to retire after a crash, the team concentrated on winning the individual race rather than the team event. In this they were very nearly successful. Les Scales, the man they wanted to see in first place, at one point took over the Yellow Jersey, eventually finished second on general classification. His team-mates, Ian Greenfield and Len West, sacrificed their own chances for the benefit of Scales.

Viking Cycle riders, who had won both the individual and team awards in the first Tour of Britain, had to be content with second placing in the team contest and fifth in the individual classification. Ian Steel, last year's winner and leader of the Viking team, was the most marked man in the whole race.

The best amateur team, without any doubt, proved to be the Romford R.C. team - the only one of its kind in the race. All other amateur teams represented areas, not individual clubs.

The Romford leader, Bill Bellamy, was holder of the Yellow Jersey for two days. Often the clubmen were very close to the team-race leaders. When Bellamy had to come out of the race with a fractured bone in the spine, the Romford lads had Dave Robinson to take over as leader - and as best amateur in the field. The club filled fifth place in the team classification, and Robinson finished ninth in general classification - best amateur by more than 25 minutes. Next amateur to him was Tony Phillips, in 21st place. Tony's club? The Romford R.C.

All this intensive team-racing made Russell's chances seem remote. When he took the lead and the Yellow Jersey after the second day, the experts - and many of the riders- said he could not hold his lead. When he lost the lead to Bellamy - at Carlisle - and later dropped to third behind Scales and Maitland, it seemed that the stocky Bradford lad was on the way down. Yet he sprang back into the lead at Scarborough, and held it over the final three stages, never once faltering.

The phenomenal speed at which the race was run proved the downfall of many - and indicated the remarkable fitness of the 43 men who survived. The phenomenal speed at which the race was run proved the downfall of many - and indicated the remarkable fitness of the 43 men who survived.

Those who said, 'They cannot possibly keep it up,' were proved wrong. Even the riders themselves believed that the pace would slow down towards the end. But it did not. On the very last stage the leaders raced into Alexandra Palace well up on a revised schedule based on 24 m.p.h. average.

Over the whole de-neutralised section of the race, a speed of 25.4 m.p.h. was full

maintained. The average speed for the full distance, including the neutralised processions out of starting towns when no racing was allowed and the field rode slowly, was above 24 m.p.h.

This speed was something quite unheard of for road racing in Britain. Even by Continental standards it was truly remarkable.

What of the racing men themselves - the men who rode at this amazing speed for 14 days? What does it mean to take part in the Tour of Britain?

Many of the men were amateurs. For them, it meant taking time off from work in order to compete. For these fellows, it was their summer holiday. For many, there will be no holiday with wife or family, this year.

Their machines, too, had to be paid for out of their own pockets. These machines cost anything up to £60 each. Then there are spare wheels, tyres, spokes and small parts, all be provided.

When the race set off from Hastings, the field was worth, in machines alone, more than £4,800. Behind them were cars and vans carrying spare machines and parts worth more than £3,200. The riders themselves carried spare tubular tyres either round their shoulders or fixed behind the saddle. These alone were valued at £900.

In addition to all this, two service vans carried spares valued at more than £2,000 each. Food worth £210 was handed up to riders during the actual racing ; feeding bottles, musettes (the small bags used for handing up food), sponges and buckets amounted to another £200. Two thousand hotel beds were used during the 16 days by riders and officials.

The organisation of this great enterprise was in the hands of the Daily Express and the British League of Racing Cyclists, under whose rules the race was run.

Of all the great riding during the Tour, Ken's will stand out for many, many years as one of the most courageous and most daring. In the following pages you are presented with the account of the race from stage to stage. Read the story of Ken's performance and the riding of other competitors in this greatest British cycle race ever presented - the Second Daily Express Tour of Britain.

|

THE Second Daily Express Tour of Britain, the greatest cycle race Britain had ever seen, ended in Alexandra Palace, London, on September 6th. It was won by the man the experts said 'could not possibly win', Ken Russell, romping home on a borrowed machine for the final 30 miles, swung into the Palace grounds to the deafening roars of thousands of spectators, and finished in second place on the last stage and first place on overall general classification.

THE Second Daily Express Tour of Britain, the greatest cycle race Britain had ever seen, ended in Alexandra Palace, London, on September 6th. It was won by the man the experts said 'could not possibly win', Ken Russell, romping home on a borrowed machine for the final 30 miles, swung into the Palace grounds to the deafening roars of thousands of spectators, and finished in second place on the last stage and first place on overall general classification.

The phenomenal speed at which the race was run proved the downfall of many - and indicated the remarkable fitness of the 43 men who survived.

The phenomenal speed at which the race was run proved the downfall of many - and indicated the remarkable fitness of the 43 men who survived.