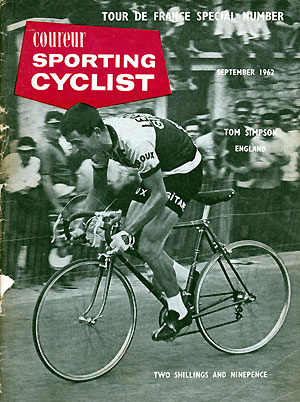

1962 49th Tour de France

|

Credit: Sporting Cyclist, September 1962, Vol 6 No 9

|

|

Editorial

THE first trade team Tour de France for 32 years went off smoothly. It was a far better race than in 1961, and might have been the greatest ever but for the unfortunate accident to Rik Van Looy at roughly "half-time." As you will read later in this special Tour number, I think the individual winner would have been the same, even if Van Looy had still been there at the Pare des Princes.

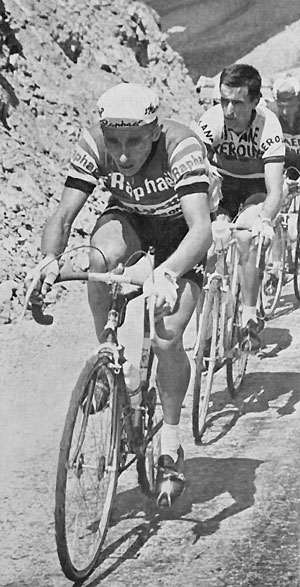

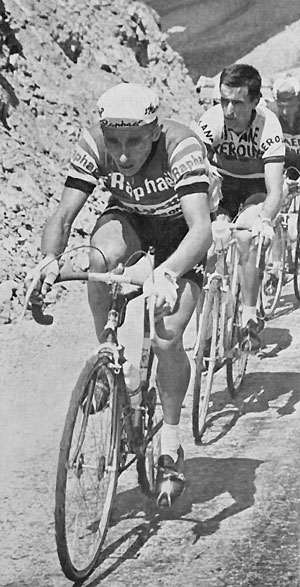

Jacques Anquetil, the elegant and rather frail-looking young fellow we saw in a lounge suit at the Royal Albert Hall last November, was a veritable power-house on his bicycle. He has now won three Tours de France in a very different manner from that employed by Louison Bobet and Fausto Coppi, but his place among the giants in Tour history is unquestioned.

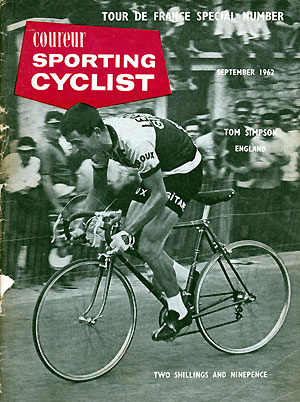

Some nations-Holland and Spain, for instance-would this year have preferred the old system of national teams, but we in Britain have no complaints. Last year we had twelve starters and three, finishers. In the 1962 Tour there were but two, Alan Ramsbottom and Tom Simpson, at Nancy - and they were both there at the finish at the Parc des Princes.

To suggest that Simpson would never have taken over the yellow jersey without trade team support would be to forget that he very nearly brought it off two years ago as a member of the British national team. This year Tom finished ninth on the first day, and not once throughout the whole Tour was he out of the first ten on general classification. This was a remarkable feat, for which some of the credit must go to his astute directeur sportif, Raymond Louviot, and the rest of the Gitane team. But it was Tom who was the real hero of them all!

J. B. WADLEY

|

|

|

Yes, Jacques, You Were All Right - and so were you, Tom!

REGULAR Tour fans will understand the point behind the title of this article. They will remember our 1961 September issue which began with a summary of the race which Jacques Anquetil dominated from the first day. Above a photograph of a small peloton climbing a mountain was the title "I'm all right - Jacques," and the theme of the summary - indeed the theme all the way through the issue - was that once Anquetil had taken the maillot jaune at Versailles, all he had to do was to control the race for three weeks.

Of course the execution of that plan was a tremendous athletic achievement which I heartily applauded. But I also remarked that if every Tour were so constructed, then the days of the race would be numbered. The public had lost interest after a week.

The fact that Anquetil won in an entirely different way this year is not because he had been asked to do so by the organisers. He was not like the great sprinter Scherens who started his career by winning all his races from the front, then switched to his sensational last-100 metres rush from behind which went down so much better with the public. Anquetil rode a different race this year because it was a different kind of Tour against different opponents.

The Rouen rider is not a sentimentalist. He does not ride to the public - there were some hisses and boos directed at him at the Parc des Princes - and if conditions were different in 1963, then he might well try again to hold the lead from the very first day. Anquetil would not worry if the race became dull. If his efforts were finally crowned with success, then he would have won the Tour de France three years in succession (only Louison Bobet has managed that so far) and for the fourth time in all (which nobody has yet done).

There will be time enough to speculate on what might happen in 1963. We have barely space to analyse how Anquetil won this year. I must say right away that his was a magnificent victory, planned as far back as January when the formula was first announced, and carried out with mathematical accuracy. What makes me say "You were all right Jacques" was not only his riding during the Tour, but the way in which he rode himself back to form and confidence in the month preceding the race. There will be time enough to speculate on what might happen in 1963. We have barely space to analyse how Anquetil won this year. I must say right away that his was a magnificent victory, planned as far back as January when the formula was first announced, and carried out with mathematical accuracy. What makes me say "You were all right Jacques" was not only his riding during the Tour, but the way in which he rode himself back to form and confidence in the month preceding the race.

Anquetil's sensational retirement on the last day of the Tour of Spain - on May 13 - was followed by a fortnight's rest on doctor's orders, and then an anxious period of rehabilitation in which the seven-day Dauphine Libere, the French road championship, and the Manx Premier road race all played their part.

There was, of course, a moral as well as physical crisis to overcome, and when Anquetil's life story is written, that Isle of Man race will have its place. For on the windswept Clypse circuit Anquetil found his real form; and in the Douglas Bay Hotel he found that his team-mate Rudi Altig was not such a bad fellow after all, and that he could count on his loyal help in the Tour.

Why should Anquetil want Altig by his side in the Tour de France? Had he not personally picked the German to help him in the Tour of Spain, and then found Altig snatching victory from under his nose? Why should Anquetil want this man - whom he accused of "double crossing" immediately after the Vuelta in his Tour team?

The explanation is simple. Anquetil knew that Altig could not be the slightest danger to him in the mountain stages of the Tour, but would be an enormous help on the flat. Anquetil was only worried about one man in the 1962 Tour and that was Rik Van Looy. In the pre-race calculations, Anquetil was prepared to credit Van Looy with as many as eight "flat" stage wins and the corresponding eight minutes of bonus time. The Frenchman was confident he could wipe out those eight minutes without much trouble in the 129.25km of individual time trial racing.

But Anquetil was shrewd enough to know that with Altig in the Tour, Van Looy would not win eight stages. He was as certain of Altig's extraordinary end-of-flat-stage finishing powers as he was of his inability to climb mountains. Moreover, there was also a short team time trial, in which the powerful Altig would help the Helyett team to keep within a minute or so of Van Looy's Faema team. And in a serious chase - whether in the front trying to force a break, in the middle bridging a gap, or at the back getting back after a puncture - in a serious chase, what better wheel for Anquetil to take than that of Altig, three times pursuit champion of the world?

|

|

|

|

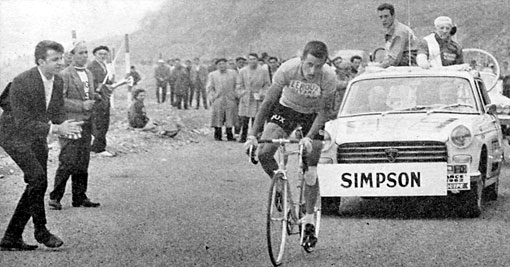

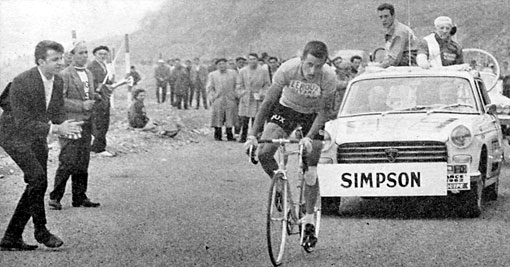

Jacques Anquetil leads Tom Simpson

|

|

|

|

The point was proved from the first day at Spa, when Altig won the sprint from Darrigade and Van Looy, and confirmed at Amiens two days later. Although Van Looy kept on trying to win those sprints, I believe he sprinted with less conviction through knowing he not only had to beat his arch rival Vannitsen to the line, but the rapid Altig as well.

Van Looy retired from the race at exactly the half-way mark, after 11 flat stages, and without a single win. Was the world champion therefore to be written off as a complete failure in a race which all Belgium was counting on his winning? Not at all. After Anquetil he was the man of the race, and in some people's book comes even before the winner.

Quite apart from the outstanding personality of the man - he appealed to the crowd in the manner of Coppi and Bobet - Van Looy's influence on the running of the race was enormous. Those very fast opening stages of 25, 26, 27 and even 28 m.p.h. were often due to his attacks or counter-attacks, and it was both ironical and just that at St. Nazaire, at the end of the first week's racing, Van Looy still hadn't won his stage but was awarded the prize for the most aggressive riding of the day.

Whenever Van Looy attacked there was panic in the bunch behind, and times without number Altig and Anquetil (and Simpson) were the men who brought him back. And yet Van Looy continued with his attacking game which at times seemed almost novice-like in its simplicity. But if Anquetil is a shrewd rider, so is Van Looy, and judged from a team angle it had its effect, for while the heads were marking the world champion, his team-mate Schroeders was able to slip into the yellow jersey for a day or two, and Planckaert moved up gradually to the position from which he took over the race leadership for a whole week.

That Van Looy should have been so brilliant on the flat was no surprise, but what we were waiting for was his riding in the mountains. Then almost within sight of the Pyrenees came the crash that put him out of the race. We were not to know it at the time, but there roughly at half time in this great match, the outstanding player was injured and carried off in a helicopter. That first half had been brilliant; the second half in comparison was dull even though the eventual result, Anquetil vainqueur, was a just one. That Van Looy should have been so brilliant on the flat was no surprise, but what we were waiting for was his riding in the mountains. Then almost within sight of the Pyrenees came the crash that put him out of the race. We were not to know it at the time, but there roughly at half time in this great match, the outstanding player was injured and carried off in a helicopter. That first half had been brilliant; the second half in comparison was dull even though the eventual result, Anquetil vainqueur, was a just one.

For the moment we will leave aside what might have happened had Van Looy not retired, and summarise that second half, which immediately became remarkably like the 1961 Tour. Anquetil moved up to within 68 seconds of the new leader, Planckaert, after the Superbagneres hill climb, controlled the race during the two transitional stages to Antibes, never let Planckaert out of sight in the Alps, and then trounced him in the time trial.

And if Van Looy had been there? Personally, I think he would have forgotten his own ambition to win the Tour, and ridden for Planckaert. He would have attacked without cease between Luchon and Antibes, and the first 60 miles from Antibes on the Restefond stage would have been far from the 15 m.p.h. promenade that it was. Van Looy would have forced Anquetil to efforts that would have made the Alpine climbs a punishment, and Anquetil might have arrived at Aix-les-Bains scared stiff of the morrow's time trial. Meanwhile Planckaert would have been playing a passive role and might have won the Tour in the last time trial instead of losing it as he did.

My own belief is that Anquetil would have been equal to the challenge, drawn on his enormous class, and shown for the first time his real ability in the mountains. (I believe equally that if there had been no time trials in this 1962 Tour he wouldhave won it just the same because he was by far the strongest rider.) But, as I have said, Anquetil is a calculator, and he won the race in his own manner. Had Van Looy been there, he would have had to win it in a different way, and his popularity would have increased enormously.

|

|

|

As things turned out, Anquetil's strength made the mountain stages a great disappointment. Let me recall that day in the Izoard pass at the end of the great Alpine stage. We pulled up in the car at a point halfway up the pass which commanded a good view of the racers below. Eddie Pauwels was alone in the lead. Already at the vantage point was a Belgian radio commentator, whom I greeted by remarking that he would no doubt be thrilled at Pauwels' fine ride at the front.

"Thrilled?" he exploded. "No, I am not thrilled at all. I am disgusted with this so-called mountain stage. If Pauwels wins this stage then it will be a terrible thing for the Tour de France. Pauwels is a fine rider, but he is no climber; yet he has been away since he dropped Bahamontes on the descent of the Restefond. Pauwels has had five punctures and three heavy crashes. Yet he is actually gaining on Anquetil and the so-called climbers.

"Did you see the monument to Fausto Coppi down there in the early slopes? What an insult to the memory of Fausto is this stage. Did you see Louison Bobet following this stage in a Press car? What must he think of the present generation of climbers - Bobet, who constructed his great victories here on the Izoard?"

Pauwels, of course, was caught, and it was another Belgian who won the sprint at Brianqon. Was our radio friend now content. No. He was angrier than ever.

"Eight men together at Briancon. . . . Daems, a sprinter, winning the stage . . . What has the Tour come to?"

When our friend calmed down, he knew the answer as well as anybody. There are no new climbers, and the old ones, Massignan and Gaul, had been "cooked" by the early fast stages and Bahamontes was concerned only with the Grand Prix de la Montague. They were incapable of attacking Anquetil, and Planckaert was already looking forward to being second in the Tour, and had no other ambition than to keep with Anquetil, "the man who cannot drop anybody, but whom nobody of any importance drops." Only one man might have dropped Anquetil on the Izoard, and he was Poulidor. The Mercier man, however, was saving his effort for the Chartreuse stage in which he rode magnificently and made us regret more than ever his pre-Tour accident.

So there again we had an untroubled Anquetil in the mountains - and a dull race as the direct result.

And now let us study the case of Tom Simpson, who falls naturally into his place in this summary of the 1962 Tour. I have followed pretty well every stage of the Tour since 1955, and it was an immense joy to be there with Tom during his moment of triumph at Saint Gaudens. Pierre Chany was right in "L'Equipe" when he said there were tears of joy in my eyes as I watched Tom putting on that maillot jaune (I have already forgiven Pierre for describing me thus: l'ami Wadley de 'Cycling').

|

|

|

|

|

|

I was proud of our Tom for the way in which he earned the race leadership : intelligent early riding when ambitious attacks would have been suicidal . . . a brilliant opportunist slip into the break on the morning of Sunday, July 1, between St. Nazaire and Lucon, a sound afternoon time trial to La Rochelle . . . a sensibly quiet period from there until Pau - and then the big day to Saint Gaudens.

It was a pity that the jersey was lost the very next day, but at least there is consolation in knowing that Tom was knocked out in the department in which - judged as a potential Tour winner - he is weakest: climbing. This is an assessment made by somebody who ought to know, Simpson himself.

Naturally, I only know "second hand" what impression Tom's race-lead exploit created in Britain. I gather, though, that people immediately began to think he was going to win the- Tour this year. I wish I could have put over to them the point I made to a group of tourists I met in Luchon the morning after the jersey had been lost. They were far more disappointed than Tom! My friends were cricket fans, and it was easy to convey the true situation to them.

"Imagine that Norfolk or Devon or another of the minor counties were admitted to the county championship. Naturally for a start they would be near the bottom of the table, but then after eight years of steady improvement, this new county might rise to the top of the table half-way through the season. It would make headlines. Keen cricketers would not expect to see them there for more than three days, but would rejoice at this feat, all the same.

"It is the same with the Tour de France. Britain is a minor cycling nation in this field. We have only been in the race since 1955, and now one of our riders is at the top of the table. He won't win the Tour this year, but he has brought us nearer to the day when we shall see a British winner at the Pare des Princes".

When he found himself in third position at Brianqon, Tom's aim was to keep as near Anquetil as he could for the rest of the mass-start stages, and do a decent time trial. By so doing he would still be third in Paris. The next day, at Aix-les-Bains, he finished 4.25 minutes after Anquetil and dropped to sixth.

In the press room every night where 150 journalists write furiously for two hours and then rapidly dictate their stories by telephone - there is a mutual exchange of information. Naturally, I was always asked for news of Simpson and Ramsbottom. At Saint Gaudens they were buying me champagne; at Aix-les-Bains it was sympathy I was offered.

"Simpson - beaten, eh? Four minutes after Anquetil. But he will be sixth in Paris all the same. That is good."

"But he had trouble!" I protested. "He fell on the descent of Col de Porte, hurt his back and thinks he has fractured a finger!"

"Yes, that was a pity. But Simpson was beaten before the fall. He had been dropped on the climb. He would never have rejoined even without his fall."

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now here is a question in which Simpson himself must have the benefit of the doubt. He alone knows what he could or could not have done on that Chartreuse stage, and this is what he says:

"I am certain that without my fall I would have caught the Anquetil group on the descent of the Granier,and finished with him at Aix-lesBains."

That would have made Tom third at Paris....

But if we are going to play at "ifs," we must consider what would have happened if Van Looy had still been in the race. I have explained how he probably would have made life much more difficult for everybody in the mountains. Instead of there being a nice comfortable "packet" on the climbs for Simpson to follow, there might have been a right old battle with every man for himself. In that case I don't think Tom would have been anywhere near Anquetil on time, but there equally would have been few other riders between them on the road.

I don't think Tom will quarrel with that opinion. Even with Anquetil, Planckaert, Gaul and Co. riding en peloton, he had difficulty following them near the summits of the big cols, and used to drop off voluntarily with a kilometre to go and rejoin on the descents. It is significant that when he was dropped on the Col de Porte he had no option - he told me so himself afterwards. The reason was that Anquetil was going just that bit faster - because a dangerous man named Poulidor was away on his own in front.

There were a thousand "ifs" in this 1962 Tour, and that applying to Simpson is not without its importance. But the two big questions concern Van Looy and Poulidor. What would have happened if the world champion had not retired, and if the French star had been fully active from Nancy?

This is my summary of the 1962 Tour dealing only with the top men of the race. I say this with all respect to Alan Ramsbottom who rode a remarkably fine first Tour. I will have more to say about him in the next issue, in which I will deal with many other aspects of the Tour. Meanwhile, in the succeeding pages you can join me in a conducted Tour with pen and camera from Amiens to Paris.

J. B. WADLEY

|

|

There will be time enough to speculate on what might happen in 1963. We have barely space to analyse how Anquetil won this year. I must say right away that his was a magnificent victory, planned as far back as January when the formula was first announced, and carried out with mathematical accuracy. What makes me say "You were all right Jacques" was not only his riding during the Tour, but the way in which he rode himself back to form and confidence in the month preceding the race.

There will be time enough to speculate on what might happen in 1963. We have barely space to analyse how Anquetil won this year. I must say right away that his was a magnificent victory, planned as far back as January when the formula was first announced, and carried out with mathematical accuracy. What makes me say "You were all right Jacques" was not only his riding during the Tour, but the way in which he rode himself back to form and confidence in the month preceding the race.

That Van Looy should have been so brilliant on the flat was no surprise, but what we were waiting for was his riding in the mountains. Then almost within sight of the Pyrenees came the crash that put him out of the race. We were not to know it at the time, but there roughly at half time in this great match, the outstanding player was injured and carried off in a helicopter. That first half had been brilliant; the second half in comparison was dull even though the eventual result, Anquetil vainqueur, was a just one.

That Van Looy should have been so brilliant on the flat was no surprise, but what we were waiting for was his riding in the mountains. Then almost within sight of the Pyrenees came the crash that put him out of the race. We were not to know it at the time, but there roughly at half time in this great match, the outstanding player was injured and carried off in a helicopter. That first half had been brilliant; the second half in comparison was dull even though the eventual result, Anquetil vainqueur, was a just one.