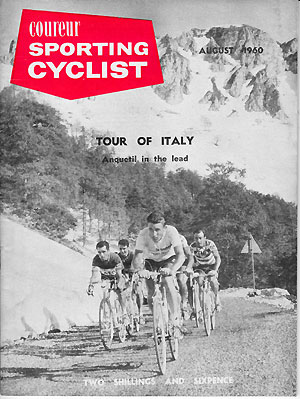

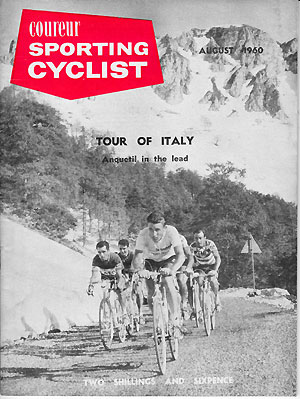

1960 43rd Tour of Italy : Giro d’Italia

Italians have won the Tour de France but a French rider had never won the Tour of Italy - until this year. This is the story of the epic victory by Jacques Anquetil in the Italian classic.

|

Credit: Sporting Cyclist,

August 1960, Vol 4 No 8

by Rene de Latour

|

|

AS many Olympic athletes and cyclists will discover soon, the Roman sun is hot. Even in May the temperature was soaring, and especially on the 19th, a great day for Italian cyclists: the start of the 43rd Giro d’Italia.

And as we assembled there in front of the Quirinal, where the "First Man" in Italy, President Gronchi, gave the field an official farewell, we thought that not only was the weather going to be hot, but the racing, too. There was a total of 140 riders, split up into 14 trade teams. Italians, Dutch, Belgian, Swiss, French, Spaniards - and one lone figure whom the newspapers described as "British." But although he is well used to this, now, Seamus Elliott still patiently points out to race organisers that he is Irish and proud of it.

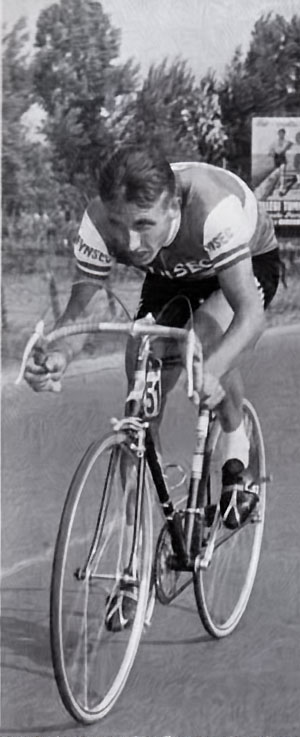

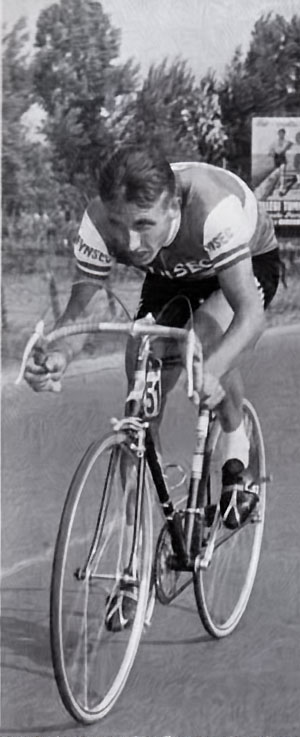

Seamus Elliott was not there to win the Giro. Not one such tiny thought entered his head. He is an unusually intelligent rider, and nobody knows better what the course d'equipe (team race) means. He knew what his job was going to be for three weeks: to protect Jacques Anquetil.

"Protecting" a rider is no easy task. It takes a strong man to stop (although that, admittedly, is easy enough), fill a bidon with fresh water, jump on the bike again and catch the field with the drink for the leader, when the pace is round about 27 m.p.h. He has to have "class," too, to perform at the other end of the peloton, by being ready to pounce on any dangerous wheel that may sprint away to try to split the field.

|

|

|

|

<< “In the lead is Seamus Elliott, loyally protecting his team-mate, Jacques Anquetil, wearing the pink jersey of leadership.”

|

|

Before the race started, there was the usual conference, presided over by the Helyett team manager, Micky Wiegant. Each member of the team was briefed, and went away knowing exactly what was expected of him.

"You're a strong finisher," Wiegant said to Elliott. "We will often need you as a domestique when things get bad. But normally you will be free to help yourself to a stage win or two if all is well." Easier said than done - thought Shay....

A year or so ago I wrote in "Sporting Cyclist" the differences between the Giro and the Tour de France. And, indeed, there are a great many differences.

In the Giro, each team has its nominated leader from the start, and most of them do not want to have a hard race all the way, as it usually is in the Tour de France. So their teammates are under instructions to "kill" the race, and not to make it.

Sometimes, of course, riders manage to break away on the flatter roads for a stage win. But the race is controlled from the bunch to such an extent that the winning margin is rarely big.

|

|

|

It started that way between Rome and Naples. Six men fought very hard, but apart from the glory and cash prizes for their success, their time reward was very small: 13 seconds on the group.

The figure "13" also applies to unlucky Elliott. He stopped behind to help the punctured Rostollan (considered a possible second leader if anything happened to Anquetil), and after a further series of mishaps, they were well behind the fast-moving field, and arrived 13 minutes after the winner.

This winner, who took the honour of being the first to wear the Pink Jersey of leadership, was Dino Bruni. who, I believe, was in the Italian team with Baldini in the 1955 Manx International. This strong, dark, lad has a good finishing sprint which, among satisfactions, won him two stages of the 1959 Tour de France.

The "heads" had been careful not to extend themselves too much - and with reason. For things were due to get really serious on the second day, on the roads adjacent to the magnificent Sorrento Bay - roads bordered by the sweet-smelling orange and lemon groves sloping up to the pure-blue sky. The riders, though, had no eyes for such beauty, nor spare breath to sniff the fragrance. Especially the two chief contestants, Jacques Anquetil and Venturelli. That day was a 25 kilometres time trial, including a tough three miles climb.

You have probably heard a little of a name Venturelli, and you may hear a great deal more. Whether or not the former shepherd boy will turn Out to be a second Fausto Coppi, I don't know. But that was what the madly excited Italian crowds were shouting.

At any rate, Venturelli looks very nice on a bike. He is fast, a good climber, and an outstanding man in a time trial.

This time trial started according to form. Over the first 15 kilometres, to the top of the climb, Anquetil displayed his best form, and was already 34 seconds up on his young Italian rival.

I followed Anquetil from the top of that climb, all the way into Sorrento. Having made the check at the hill top, I was convinced he could not be beaten, because as well as climbing strongly, he descended like the wind, too. The way he took those narrow corners, brushing walls with his shoulder, was just terrifying. Unlike the Tour de France, where there is one-way traffic (the racers and caravan), with the police co-operating, the roads are open in the Gi'ro. Anything might happen . . .

When Anquetil had finished, I dashed over to the big result board in the journalists' enclosure, and there already was his time chalked up. To my astonishment I found Venturelli had beaten him by six seconds. Anquetil, had lost 40 seconds on the five miles descent.

I found Anquetil not too disappointed. "The risks he must have taken down hill to beat me," was his comment. "He must be mad."

|

|

|

The Italians are great chalk users. While waiting for the Giro to come along, the roadside crowds pass the time pointing the names of their cycling gods on the walls and roads. Venturelli was due to be "chalked up" a great deal.

"ROMEO — FAUSTO WOULD HAVE BEEN PROUD OF YOU." "VENTURELLI — YOU'RE THE GREATEST AMONG THE GREAT." "ROMEO, THE ITALIAN SPUTNIK."

There were doubtless many others, but I've forgotten them already. The signs didn't last long .. .

Four days later Venturelli was back home in his native village, broken hearted. For hours and hours, on the road to Rietti, journalists and followers had been hovering around urging the "Sputnik" to go a little faster than the 10 m.p.h. which was all he could muster.

Poor Romeo! With a hand on his stomach he was as sick as a dog, and nothing could be done to help him. His San Pelligrino team mates were with him, and when eventually he climbed into the sag wagon, they were lost, too, it being impossible for them to finish inside the time limit.

I had a talk with Gino Bartali about Venturelli. It was the famous old campionissimo who had persuaded the young rider to turn pro.

"I have a good man here," he had said. "Poor Fausto and I both spotted him. We haven't had anybody as good for years."

But after the incident on the Rietti road, Bartali's attitude changed:

"He's got the legs, the lungs, but not the heart," he said. "I would never have quit the Giro just for stomach ache. I would have been ashamed of myself."

Yet the Italian press was not very severe with Venturelli. So much is awaited of him . . . later on.

You will not, I know, expect me to chronicle everything that happened, day by day, in the Giro. I will necessarily have to "skate" over a lot of it, pausing only here and there to recall an incident or two, before getting down to the real drama of the race.

|

|

|

I must, of course, tell you of the stage win of Seamus Elliott, every bit as important in its way, as that by Brian Robinson when he scored his first Tour de France victory two years ago at Brest. It was not, as I believe has been reported in Britain, the toughest stage of the Giro, but it was the longest. Elliott's success was the result of one of his strong end-of-race rushes for which he is so famous. In the last hour he had an epic pursuit match with Battistini, which forced him to use a 54 x 14 gear first to catch, and then drop his rival, a few kilometres from the finish.

All the Helyett team were glad Shay had pulled off the stage win. He had been working so hard for the team that he had let other stage-winning opportunities escape earlier in the race.

As they did last year, the Giro organisers included plenty of time trials. The one at Rimini was only three miles in length, with a sharp corner about every 300 yards. It was a wonder 20 riders didn't end up in hospital that day.

In the Giro, every second counts, and although you may think a three miles time trial not worth bothering about, Anquetil tried with all his might. He would certainly have won had he not had to change bikes after his chain got jammed between the two chain wheels. Surprise winner was Miguel Poblet, who was more elated by this success than if he had beaten his rival Rik Van Looy in three successive sprint finishes.

"If I really put myself out, I don't ride a bad time trial now and then," said the soft-spoken Spaniard. "It is a question of putting my mind to it."

There were 23 stages in the Giro, but so far as Charly Gaul, Anquetil and Nencini were concerned, there were no more than two or three of them likely to be of importance - such as the day of the Cervinia climb, the 68 kilometres time trial near Milan, and the long hill stages of the Dolomites culminating with the mysterious Gavia pass. The other racing hadn't much effect; the "heads" contented themselves with a cold war :

"If I'm in shape, I'll win the time trial by so much that the Giro will be finished that day," said Anquetil.

"I don't care what Anquetil will do in the time trial" said Gaul, "If I climb as well as I hope, Anquetil will be minutes behind me on the Gavia. I'll kill him the same as I did on the Little Saint Bernard pass last year. If I can get rid of my sore throat, that

is . . .

Nobody really believed Charly Gaul had a sore throat. When Anquetil saw the scarf round the Luxembourger's throat, he just laughed.

"That's one of Charly's tricks," Jacques said. "Let the road climb high enough and he'll forget he's even got a throat."

Yet soon I and other followers were to wonder if Gaul might not be ill, after all, especially on the climb of the Cervinia. This is a 15 miles test, with many a stretch looking like the roof of a house, and only a few faux plats ("false flats" or breaks in the climb), before reaching the 6,000 feet summit.

As soon as the climb started, Gaul went away like mad. Seeing Gaul in action on a mountain is well worth the journey. The former Bettembourg butcher-boy hates high gears. He will heartily whirl a 46x23 when other riders are on their 46x21's. His light legs moved so easily that when he flew away at the start of the Cervinia climb what remained of the field seemed thoroughly beaten. No doubt he was going to be first to the top once again.

|

|

|

But all was not well with Gaul. He was caught by Nencini, Hoevenaers and Massignan (the best' Italian climber), and I firmly believe Anquetil could have dropped him if he had tried.

"This hill isn't really tough enough for me," was Gaul's answer. "I'll do better in the Dolomites, I promise you.,,

The Giro had now reached the Mediterranean sea. The crowds were bigger than ever, and poor Ercole Baldini was not happy. He was so far back he hardly dare look at the general classification tables each night.

"I don't care if I'm last, though," he told me one day. "I'll keep on, as this is the only way I can get back into shape."

Baldini is the world's best paid rider. He gets £41,000 for the three years contract he signed last winter. The chalk artists got busy again:

"YOU EARN TOO MUCH; YOU EAT TOO MUCH, ERCOLE" said the notices "WIN A STAGE OR GO BACK HOME."

Baldini did not go home. He waited for the time trial at Lecco on the flat roads, to know if he were finished or not.

Britishers would find time trial riding an amazing thing in Italy. Nobody can go off course! The public often crowd on to the roads so thick that there is hardly room for the rider to pass through. It can be dangerous, but on this "his" day at Lecco, Jacques 'Anquetil did not think of danger.

Jacques Anquetil had three different "targets" in front of him. First there was the pale faced climber from Tuscanny, Massignan. Thrashing his 52x13 powerfully, Anquetil caught his man in 15 kilometres.

Next was one of his Helyett teammates, Edouard Delberghe, to whom Anquetil had said before the start:

"If I catch you, try to hang on my wheel as much as you can; you'll then finish in a high place." (That practise is common in Italian time trials, the culprit only being fined thirty shillings or so).

Delberghe, who is a very strong rider, kept ahead until 35 kilometres, when the roar from behind announced that Anquetil was nearly on him. Jacques went by a full three miles-an-hour faster, and to hang on to him, Delberghe would have needed a hook.

Then, finally, there was Gaul, who started six minutes in front. You will remember last year the same thing happened, when the on-form Luxembourger managed to stay on the wheel of the below-form Frenchman, much to his annoyance. But this year history did not repeat itself. Anquetil was irresistible; he caught and cleanly dropped his man, and went on to a tremendous win which won him back the Pink Jersey five days from the end of the Giro.

|

|

|

And so this was the general classification position after the time trial:

1 Anquetil; 2 (at 3m. 40s.) Nencini; 3 (at 4m, 19s.) Hoevenaers; 4 (at 5m. 49s.) Ronchini; 5 (at 7m. 32s.) Gaul; 6 (at 7m. 58s.) Massignan. (Elliott was at about 90 minutes!)

The Italian press was lyrical at Anquetil's feat. But Jacques was not so sure. He knew that the worst was yet to come in the shape of the Gavia climb. In much better shape than last year when Gaul assassinated him to the tune of 10 minutes on the Little Saint Bernard, Anquetil knew that physically he would be able to lose no more than four or five minutes on Gaul on any normal climb, however long or steep, and to keep Nencini under control.

But the Gavia was not a normal climb. It is the third highest pass in Europe (2,621) behind the Iseran and Stelvio—but is rarely used even for motor traffic on account of its dangers. The riders and followers were scared by advance bulletins of the unprotected 2,000 feet precipices on the descent, which worried them more than the particulars of the 1 in 5 stretches on the way up. "It is just like a Tour de France pass of 50 years ago in the days of Christophe," we were told. One newspaper said it wasn't a col, but a slaughter-house. And just to heighten the drama, a news-bulletin told us that the only inhabitants way up there in the clouds were brown bears .. .

You can understand how Anquetil felt. He knew he could hold his own on the athletic part of the stage - on the climb; but how would he fare on the acrobatic? Before the start 1,encini had stated:

"If I can top the Gavia only 100 metres ahead of Anquetil, I'll descend five minutes faster and win the Giro."

The Gavia awaited Anquetil, and the pushers awaited Nencini . . . another worry for the Frenchman.

|

|

|

"I know they'll be waiting for him," he told me. "If they could take him up in a car they would."

When the half-way mark of the Gavin climb was reached, only a handful were left. Massignan was away with a neat lead. Gaul was a minute behind with Nencini and Anquetil . . . the rest doing as well as they could.

Then Gaul went after Massignan, in his last bid to win the Giro. Then came the pushers.

Not two or three, but dozens of them, running alongside Nencini and pushing with all their might. Whoever is being pushed, whatever the nationality of the rider, this mountain pushing is a disgusting, unsporting thing. Thank goodness we have stamped it out of the Tour de France. (We must not blame Nencini, though, who is a good sportsman).

Twice after he had dropped Nencini, Anquetil had the chagrin of finding him coming back at him actually free wheeling. That, and two punctures meant that Nencini topped the Gavia 15 seconds ahead of Anquetil. Then he started his "death dive," and not even Nencini himself can say how near he came to disaster on that frightful drop into Bormio. Nencini didn't get five minutes out of Anquetil, but he gained alarmingly on the drop.

On the line. after Nencini was in, we awaited in an agony of suspense. But to our relief in came our Jacques at the end of the most important day of his racing life.

"You've done it Jacques," we shouted as Wiegant helped him from his bike. "You've still got 28 seconds over Nencini - you've won the Giro!"

Anquetil was calm. In actual fact he hadn't won the Giro. There was another day to go. Over 120 miles to Milan. He led by 28 seconds - ust over 300 yards. A bad spill could still lose him the race. But when the Helyett veteran Couvreur came in he summed the situation beautifully:

"Twenty eight seconds, 28 minutes, 28 hours, what does it matter?" said Couvreur. "You'll arrive at the Vigorelli with all us Helyetts protecting you as winner of the Giro."

Anquetil did arrive safely in Milan, the first Frenchman to win the Italian classic, and we found that Anquetil needn't have worried one bit on the last day.

For officials stated that if Nencini somehow had given Anquetil the slip on the last day and finished 29 seconds ahead he still would not have won the Giro. He would have been disqualified for having been pushed up the Gavia.

"It was a disgrace to Italian sport," they agreed.

|

|