|

A Look Over the Giro A Look Over the Giro

by David Armstrong

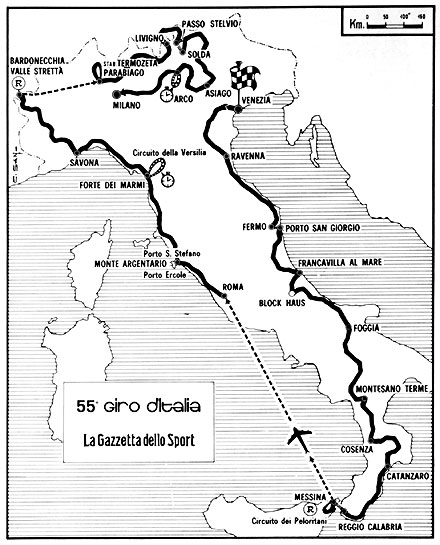

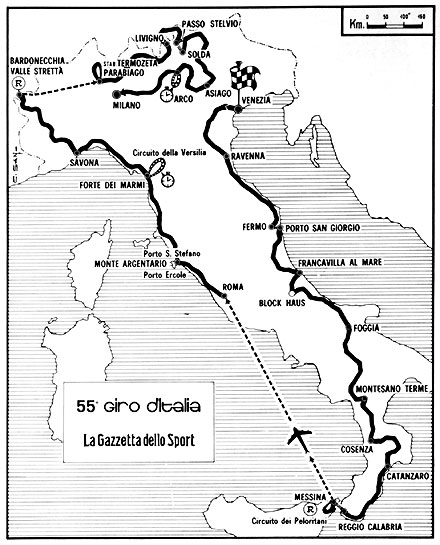

THE 55th Tour of Italy will cover 2,371 miles in 20 stages. There will be 36 miles of time trials divided into two separate tests on June 2nd (each of about 12 miles) and a further 12 miles on the penultimate day of the race. All three time trials are on circuits, as are two road stages, one of 69 miles based on Messina (Sicily), and 94 miles at Parabiaco, immediately before the final mountain stages.

If the mountainous content of the race seems reduced, in comparison with recent years, stage finishes at the summit of the Block Haus (6.500 ft.) in the Apennines, at Bardonecchia (4,300 ft.) and—the supreme test—at the top of the Stelvio Pass (9,036 ft.) will still settle the race in all probability.

Two of these summits have been of great importance in recent years. The Block Haus gave Eddy Merckx his first stage victory in the year of his apprenticeship, 1967, when he finished ninth overall and confounded many pundits by not only surviving the mountains but winning one of the key mountain stages.

The Stelvio, on the other hand was the graveyard of Van Looy's Giro ambitions. The Emperor had been King of the Mountains the year before, and had now come back to Italy to win. Holding himself well in check in the first fortnight, he then took three stages out of five, and was within five minutes of race leader, Arnaldo Pambianco, as the field approached the Stelvio. Attacking in the valley roads before the foot of the pass, Van Looy took the favourites by surprise. At the first of the 48 hairpin bends he was two minutes clear. With only five of the 20 kilometres left, he was race leader on the road by five minutes. And then he cracked. Suddenly, and with no false melodrama. The Stelvio had proved too much; and, although Van Looy recovered to win another stage and finish seventh overall, he had been beaten only by the last thousand feet of the highest pass in Italy.

It is doubtful whether there is anyone riding in the 1972 Giro who dare attack Merckx on the Stelvio; most must be praying that the race is settled one way or another long before the giant pass is reached. And yet the course is not particularly selective.

Starting in Venice the race will follow the Adriatic coast for three days, with an occasional incursion into the hills. After the climb to the Block Haus comes another easy half-day to Foggia. Two hilly days lead to Catanzaro, on the 'instep', followed by a day along one of the world's most magnificent roads, the corniche to Reggio.

After this stage come three features of the modern Giro: a circuit race, a rest-day and a trip by plane to the next starting-point, in this case Rome. The tendency to take the race into Sardinia and other remote corners has been stopped and the only intermediary journeys during the 1972 race will take place on the two rest days.

The resumption of racing sees the field taking the Mediterranean coast this time, for an easy day to Monte Argentario, on the Torre Ciana peninsula. Then it's back to the coast and a ride to Forte dei Marmi, and two separate time trials. One more day on the coast ensues before the second major day of climbs to Bardonecchia, and another transfer during the rest day, this

time to Parabiaco, for another circuit race.

For the last few days the organisers have sought to cancel out the many days of easy riding, by taking the race over a succession of passes on the Swiss and Austrian frontiers. Livigno, where the next stage ends, is high in the hills and this is followed by a day of four passes, culminating in the Stelvio itself. No respite the next day, as the race winds back towards Milan, by a series of minor passes. To make sure that nobody has been slacking the penultimate stage of 115 miles is followed, the same day, by another short time trial, and then comes the traditional final run into Milan. All in all, a deceptive race: all eyes will be-on the Block Haus, Bardonecchia and the Stelvio, and it is certain that the latter will split the field completely, but there is every likelihood that other stages, such as those finishing at Montesano, Catanzaro and Livigno, will help to decide the outcome of the race.

The 64,000-dollar question, of course, is who is going to win, and the answer must be Eddy Merckx. For the second time he hopes to do the Giro-Tour double: he will not wish to be too prodigal of his efforts, and this itinerary lends itself perfectly to his hopes, with much easy riding during the first fortnight, but regularly spaced obstacles which should allow him to recoup any time lost, and the big showdown in the Dolomites in the last few days, when he should be at his strongest. As there are almost three weeks between the end of the Giro and the start of the Tour, the double appears well within his reach.

His greatest rivals ought to be Gimondi, now free of his unhappy association with Motta (which probably cost him last year's race), and Gosta Petterson, 1971 winner. I would take these two to fill the next two places, provided that they can escape the moments of inattention which helped to relegate Gimondi to seventh in 1971, but there should be no doubt about the identity of the winner, with Eddy Merckx minutes clear well prepared for his duel with Ocana.

|

A Look Over the Giro

A Look Over the Giro